The New Quantum Race Evaluating the Next Generation of Qubit Architectures

Quantum computing is often described as a dramatic departure from classical information processing, yet its foundations lie in the strange and elegant rules of quantum mechanics. The QCGuy article Quantum Mechanics The Basis of Quantum Computing introduces these principles with clarity, explaining how superposition, entanglement and the probabilistic nature of quantum states enable behaviours that classical systems cannot reproduce. Building on this, the companion article Quantum Computing The Inner Workings explores how these principles translate into qubits, gates, circuits and the software layers that orchestrate them. Together, these pieces provide the conceptual and operational backdrop for understanding the hardware landscape that follows.

For many years superconducting circuits dominated the field. They delivered the first demonstrations of quantum advantage and achieved the highest physical qubit counts. However, as the industry has matured, the limitations of this approach have become increasingly apparent. These systems require extreme cooling, occupy significant physical space and suffer from noise levels that make large scale error correction extremely challenging. The focus is now shifting away from celebrating raw qubit numbers and towards identifying architectures capable of producing the first reliable logical qubit.

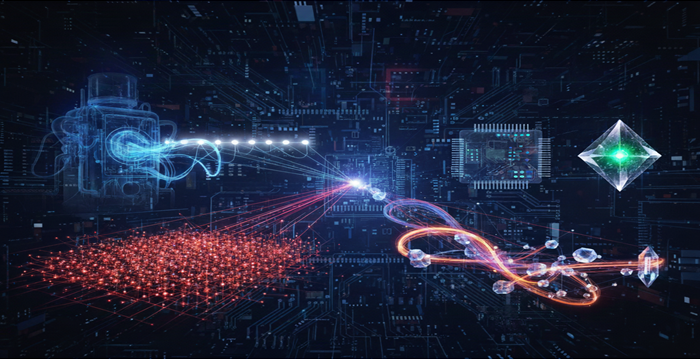

This shift has opened the door to a genuine contest between fundamentally different qubit technologies. Each contender draws upon the same quantum principles described in the QCGuy articles, yet each interprets and engineers those principles in a distinct way. The result is a diverse landscape of approaches, each balancing fidelity, scalability and practicality in its own manner.

The Contenders Fidelity and Scalability in Tension

The central challenge in quantum hardware is balancing two competing demands. Fidelity measures how accurately qubits can be controlled, while scalability determines whether millions of qubits can eventually be interconnected. No architecture excels at both, which is why the field remains wide open.

Trapped Ions The Precision Specialist

If superconducting qubits are the fast but temperamental sprinters of the quantum world, trapped ions are the meticulous precision engineers. Companies such as IonQ and Quantinuum suspend individual atoms, often ytterbium or barium, in electromagnetic traps within an ultra high vacuum. Qubits are encoded in the atoms electronic energy levels and manipulated using finely tuned lasers.

The primary strength of this approach is fidelity. Trapped ions currently achieve the lowest two qubit gate error rates of any platform, placing them closest to the thresholds required for effective quantum error correction. Their weakness lies in scalability. Long chains of ions are difficult to control, and physically shuttling ions to enable interactions introduces bottlenecks. While trapped ions excel at precision, expanding them into very large processors remains a formidable engineering challenge.

Neutral Atoms The Scalable Array

Neutral atom systems, developed by companies such as QuEra and ColdQuanta, represent one of the most promising routes to large scale quantum hardware. Instead of trapping charged ions, these systems use optical tweezers to arrange electrically neutral atoms into highly regular grids.

The advantage is density. Because neutral atoms do not repel one another, they can be packed closely together, enabling arrays containing hundreds or even thousands of qubits. Interactions are triggered by exciting atoms into Rydberg states, which dramatically increase their size and interaction range.

This architecture offers exceptional scalability, but it is still relatively young. Gate speeds, control precision and error rates continue to improve, but they have not yet matched the performance of trapped ions. Even so, the potential for massive parallelism makes neutral atoms a compelling contender.

Solid State and Specialised Systems

While trapped ions and neutral atoms rely on isolated atomic systems, other approaches embed qubits directly into solid materials, leveraging decades of semiconductor innovation.

Silicon Spin Qubits and Diamond NV Centres

Silicon spin qubits, pursued by companies such as Diraq and Intel, aim to build quantum processors using the same fabrication techniques that produce classical microchips. These qubits store information in the spin of a single electron confined within a silicon structure. The appeal is industrial scalability and compatibility with existing manufacturing infrastructure. However, these systems still require cryogenic cooling and currently exhibit higher error rates than trapped ions.

Diamond nitrogen vacancy centres take a different approach. A defect in the diamond lattice creates a protected electronic spin state that can function as a qubit. These systems offer remarkably long coherence times, even at room temperature, making them ideal for sensing and quantum memory. Integrating them into large scale, universal quantum processors remains a significant challenge.

Photonic Systems and Quantum Annealers

Some architectures depart entirely from the universal gate model. Photonic quantum computing, championed by companies such as Xanadu, uses photons travelling through optical circuits. Photons are naturally resistant to decoherence and are well suited to networking and communication tasks. Photonic systems excel at specific workloads, such as sampling and linear algebra, but are not yet competitive for general purpose quantum algorithms.

Quantum annealers, such as those produced by D Wave, are already commercially available. They are not universal quantum computers but are highly effective for solving certain optimisation problems by mapping them onto the Ising model. The system then evolves towards its lowest energy state, which represents the optimal solution. While powerful for specific tasks, annealers cannot run the full range of quantum algorithms.

The Verdict a Field in Transition

Superconducting circuits still hold the record for the largest physical qubit counts, but the industry is no longer focused on raw numbers. The true milestone is the creation of the first logical qubit, one that is protected by error correction and capable of reliable computation.

Whether the winner emerges from the high fidelity trapped ion camp, the massively scalable neutral atom approach or the industrially compatible silicon spin platform remains to be seen. What is clear is that the next phase of quantum computing will be defined not by noisy intermediate scale devices but by the architectures that can cross the threshold into genuine fault tolerance.